Often overlooked as uniform, utilitarian and uninspiring, precast concrete can make for a very compelling facade system and material finish. Featured here is one case study use of precast.

The Sphere Building of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is a 150′ diameter concrete shell structure housing a 1000-seat state-of-the-art theater-in-the-round. Daniel Hammerman led the effort for RPBW in an exceptionally collaborative process with Willis Construction Company developing, coordinating, and realizing the precast concrete scope.

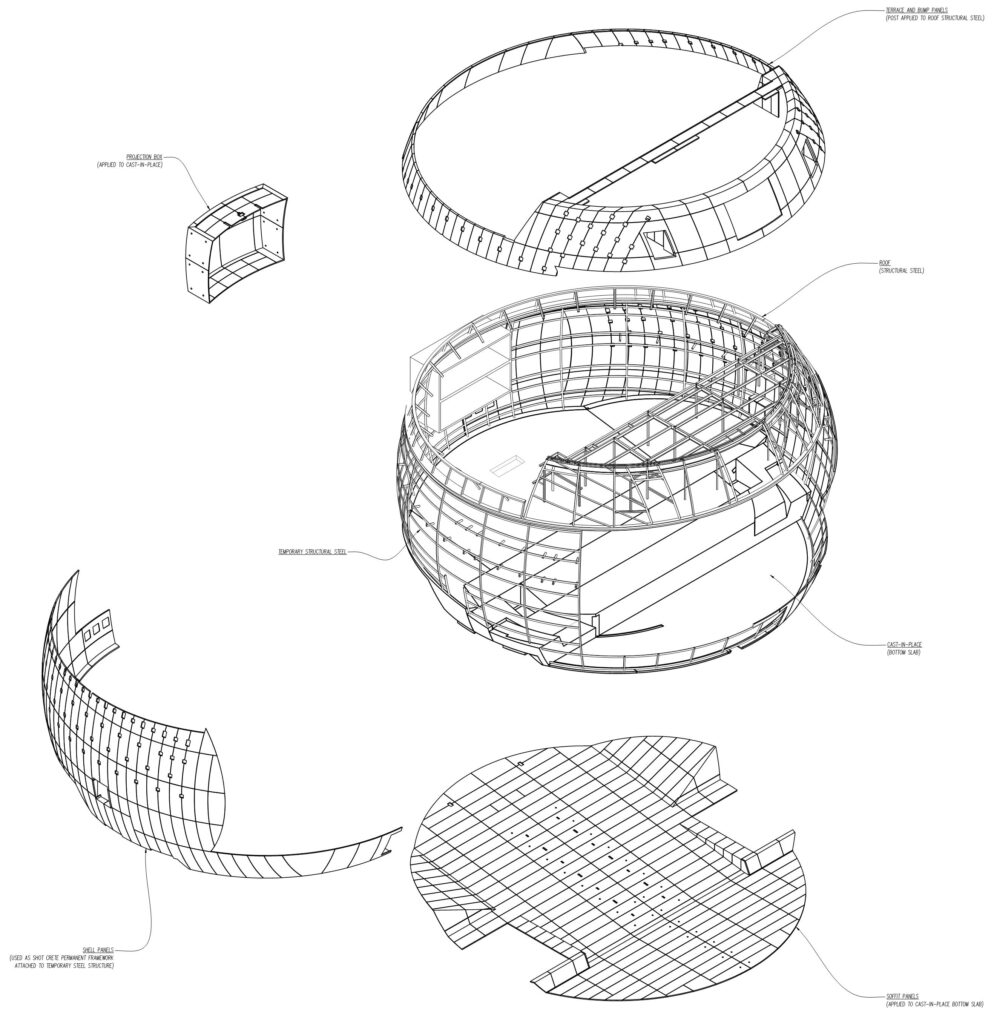

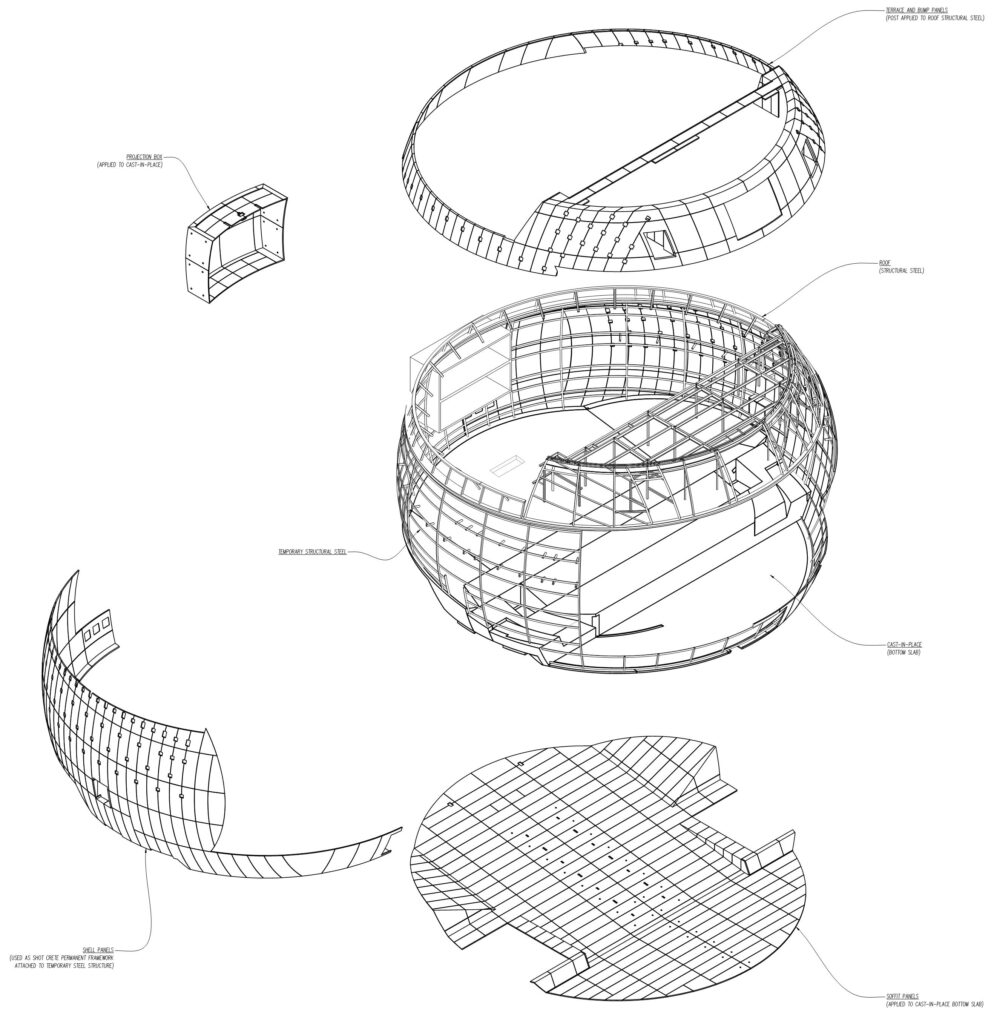

While originally conceived as an exposed cast-in-place structure, we took the highly inventive approach of erecting precast panels and using them as one-sided formwork for the structural shotcrete shell cast up against them. This offered a few distinct advantages over traditional sitecast concrete. Spherical formwork would have been prohibitively expensive for carpenters to fabricate and assemble onsite for each pour, where time is precious, as well as vulnerable to imprecise execution, not to mention wasteful of formwork material.

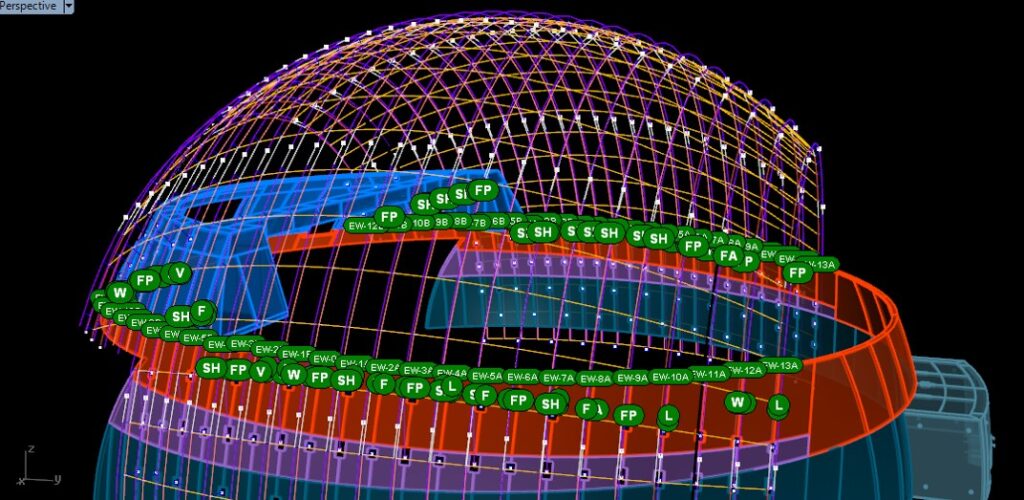

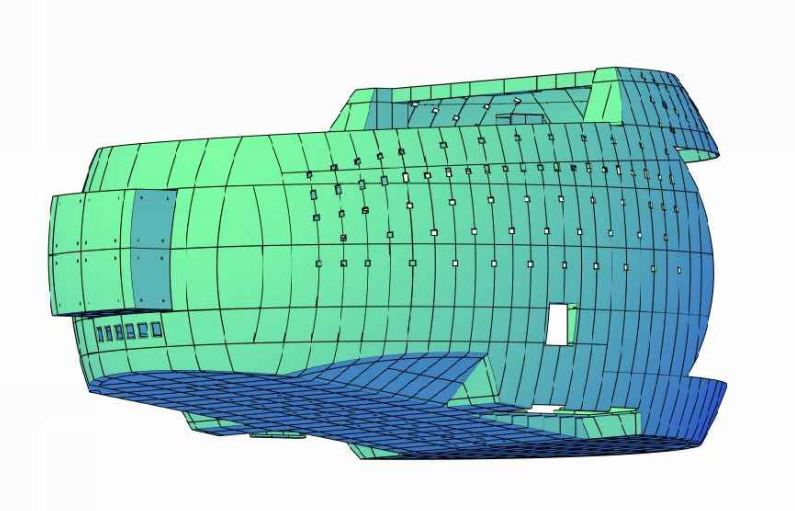

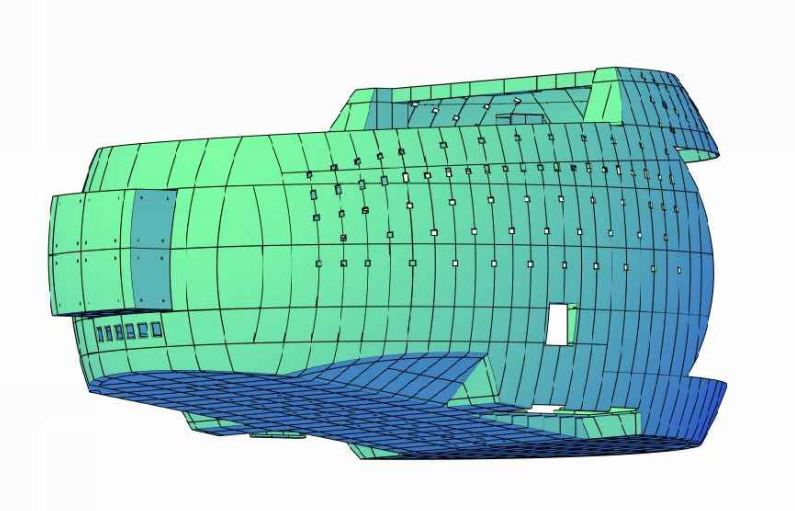

Precast allowed for better and more cost-effective QC of finish quality, tighter tolerances and geometry control to ensure a perfect sphere, including extensive coordination with many other trades’ pre-fabricated connections and penetrations. It also allowed efficient use of material, with 727 total panels cast on only 30 base molds. Though there were many unique panels (578), the consistent radius of the sphere allowed molds to be used many times with only adjustment of edge forms and blockouts.

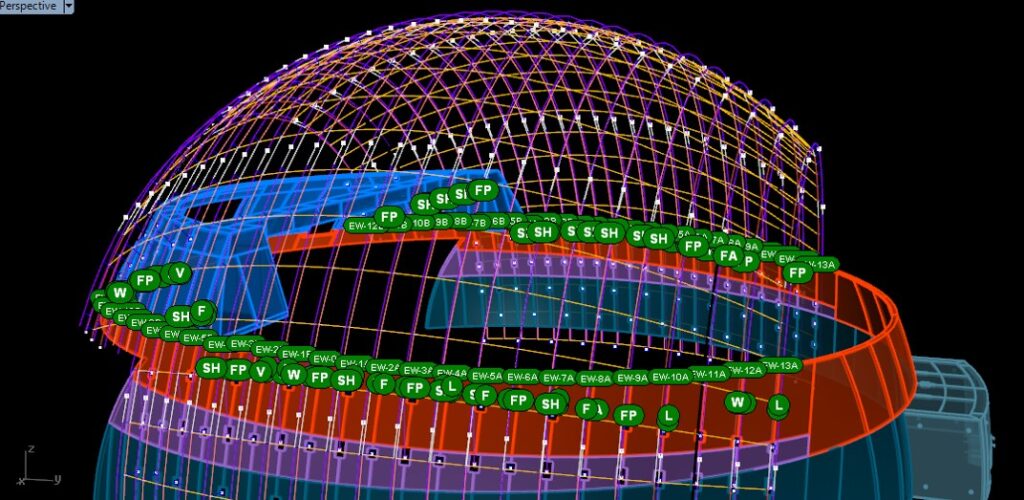

Once onsite, the 1-2 ton precast panels were erected on temporary tube steel framing, with many unique connection brackets developed by Willis, allowing installers to carefully adjust each panel from behind in every axis at multiple points, to correct global positioning (confirmed with Total Station and eyeballs), ensure perfectly spherical geometry of the envelope, consistent reveal joint profiles, and centered fit of blockouts. Countless unique blockouts, joints, and other conditions had been carefully coordinated in advance through weekly meetings and frequent exchange of design and fabrication BIM models between the architect, precaster, and other trades as they came on board and developed their systems.

As each row of precast was set in place, other trades followed swiftly behind to install their components in a tightly choreographed sequence—façade glazing embeds, rebar, electrical conduit, sprinkler lines, and lastly shotcrete was placed against the precast, which acted as a one-side form. Precise precast execution allowed for efficient construction of a building where all the systems work tightly together with technical elegance.

Precast engineering had to account for wet (curing) and final load of the typically 2-foot thick shotcrete shell structure poured up against it. While the 4” thick, 7000-psi precast panels acted as integral, permanent formwork, we wanted to avoid any inevitable cracking in the structural concrete directly translating through to the precast panels. To that end, a bond-breaker barrier was liquid-applied to the back side of the panels in the shop. Together with caulking between panels, the precast layer also acts as the waterproofing of the theater envelope.

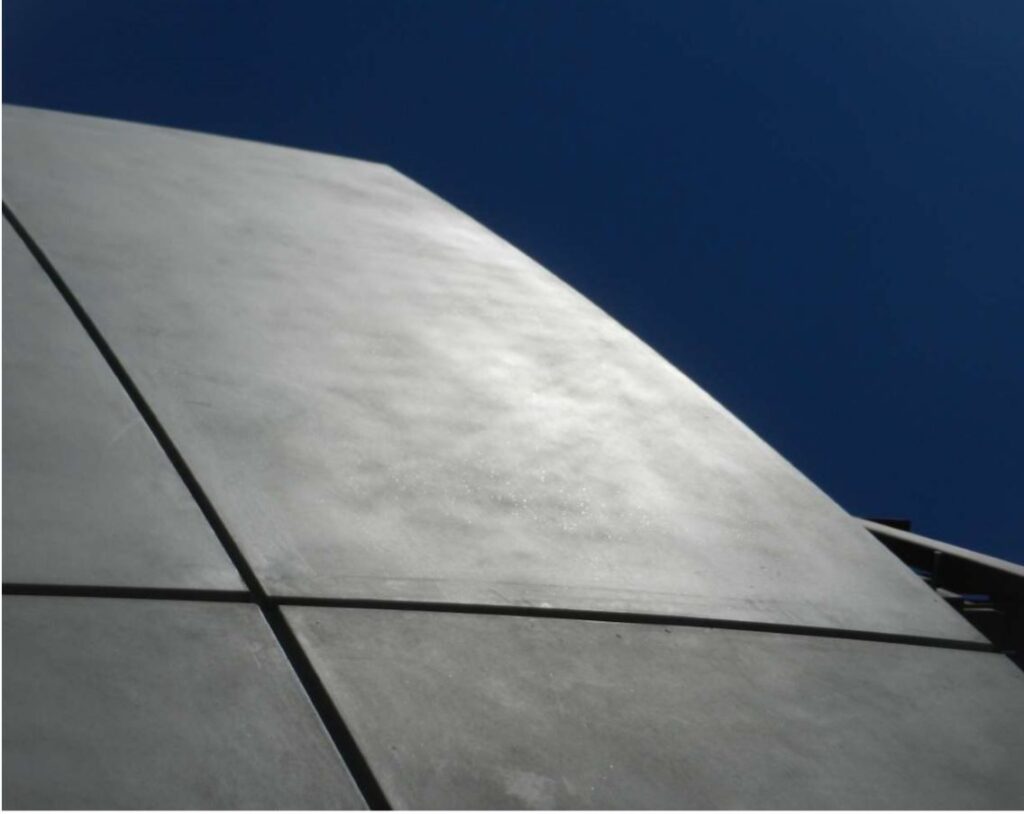

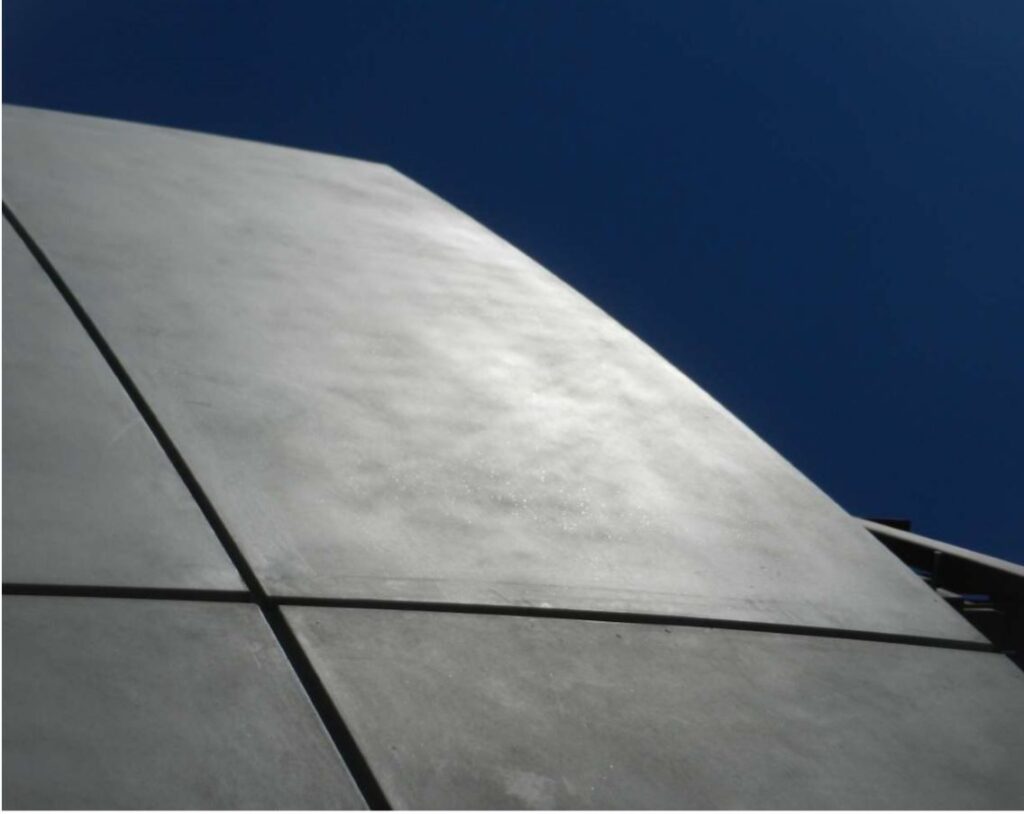

Besides the pragmatic benefits of precast concrete, we still desired some (controlled) variation of finish achievable with well-made cast-in-place architectural concrete, but less common in precast, which typically prizes a consistent, uniform look of factory-made cladding panels. We looked to the sitecast concrete of the Kimbell Art Museum Expansion as a reference. We sought a similarly luminous quality, neutral light gray tone, and the subtle mottling and almost stone-like variation that tells a story of how the material is made, poured, cured, reinforced. Collaboration with the precaster, research, samples and mockups helped identify and refine techniques to achieve the intended finish appearance.

We changed two standard fabrication practices. For their concrete mixes, precasters typically develop a formula using white cement and color additives to guarantee precise color consistency. In our case, the first samples used white cement with a bit of black pigment to achieve the desired light gray simulating traditional concrete. However, it was too perfect. The overly flat and monolithic appearance was almost plaster-like in appearance, especially seen from a slight distance. To achieve the lively, mottled look of the handcrafted material, we needed to use standard gray cement rather than whitewashing everything with the white cement. But to avoid excessive variation and potential checkerboarding, we identified a source of consistent color aggregate that we were able to stockpile and use for all the panels.

Also rather than a typical sandblast finish, which erases the flaws but also the character, we used an “as-cast” finish which imparted a slightly luminous surface quality, and allowed some of the natural variation to telegraph through the surface. Molds were carefully built, with crisp carpentry, sealed joints, casting surfaces sanded smooth and coated in epoxy resin, to ensure a high quality finish out of the mold without post-production. The gentle sheen on the soffit panels above the piazza in particular brings fantastic daylight and reflections underneath the mass of the sphere, helping create a wonderfully welcoming public plaza (underneath approximately 12,000 tons of concrete).

More on the award-winning precast linked here.

Often overlooked as uniform, utilitarian and uninspiring, precast concrete can make for a very compelling facade system and material finish. Featured here is one case study use of precast.

The Sphere Building of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is a 150-ft diameter

concrete shell structure housing a 1000-seat state-of-the-art theater-in-the-round. Daniel Hammerman led the effort for RPBW in an exceptionally collaborative process with Willis Construction Company developing, coordinating and realizing the precast concrete scope.

While originally conceived as an exposed cast-in-place structure, we took the highly inventive approach of erecting precast panels and using them as one-sided formwork for the structural shotcrete shell cast up against them. This offered a few distinct advantages over traditional sitecast concrete. Spherical formwork would have been prohibitively expensive for carpenters to fabricate and assemble onsite for each pour, where time is precious, as well as vulnerable to imprecise execution, not to mention wasteful of formwork material. Precast allowed for better and more cost-effective QC of finish quality, tighter tolerances and geometry control to ensure a perfect sphere, including extensive coordination with many other trades’ pre-fabricated connections and penetrations. It also allowed efficient use of material, with 727 total panels cast on only 30 base molds. Though there were many unique panels (578), the consistent radius of the sphere allowed molds to be used many times with only adjustment of edge forms and blockouts.

The 1-2 ton precast panels were erected on temporary tube steel framing, with countless unique connection brackets developed by Willis, allowing installers to carefully adjust each panel from behind in every axis at multiple points, to correct global positioning (confirmed with Total Station and eyeballs), ensure perfectly spherical geometry of the envelope, consistent reveal joint profiles, and centered fit of blockouts. Countless unique blockouts, joints, and other conditions had been carefully coordinated in advance through weekly meetings and frequent exchange of design and BIM models between the architect, precaster, and other trades as they came on board and developed their systems. Once each row of precast was set, other trades followed behind to install their components—façade glazing embeds, rebar, electrical conduit, sprinkler lines, and lastly shotcrete was placed against the precast, which acted as a one-side form.

Precast engineering had to account for wet (curing) and final load of the typically 2-foot thick shotcrete shell structure poured up against it (at many vectors). While the 4” thick, 7000-psi precast panels acted as integral, permanent formwork, we wanted to avoid any inevitable cracking in the structural concrete directly translating through to the precast panels. To that end, a bond-breaker barrier was liquid-applied to the back side of the panels in the shop. Together with caulking between panels, the precast layer also acts as the waterproofing of the theater envelope. The precision of the precast execution allowed for the efficient construction of a building where all the systems work tightly together with technical elegance.

Besides the pragmatic benefits of precast concrete, we still desired some (controlled) variation of finish achievable with well-made cast-in-place architectural concrete, but less common in precast, which typically prizes a consistent, uniform look of factory-made cladding panels. We looked to the sitecast concrete of the Kimbell Art Museum Expansion as a reference. We sought a similarly luminous quality, neutral light gray tone, and the subtle mottling and almost stone-like variation that tells a story of how the material is made, poured, cured, reinforced. Collaboration with the precaster, research, samples and mockups helped identify and refine techniques to achieve the intended finish appearance.

We changed two standard fabrication practices. For their concrete mixes, precasters typically develop a formula using white cement and color additives to guarantee precise color consistency. In our case, the first samples used white cement with a bit of black pigment to achieve the desired light gray simulating traditional concrete. However, it was too perfect. The overly flat and monolithic appearance was almost plaster-like in appearance, especially seen from a slight distance.

To achieve the lively, mottled look of the handcrafted material, we needed to use standard gray cement rather than whitewashing everything with the white cement. But to avoid excessive variation and potential checkerboarding, we identified a source of consistent color aggregate that we were able to stockpile and use for all the panels.

Secondly, rather than a typical sandblast finish, which erases the flaws but also the character, we used an “as-cast” finish which imparted a slightly luminous surface quality, and allowed some of the natural variation to telegraph through the surface. Molds were carefully built, with crisp carpentry, sealed joints, casting surfaces sanded smooth and coated in epoxy resin, to ensure a high quality finish out of the mold without post-production.

The gentle sheen on the soffit panels above the piazza in particular brings fantastic daylight and reflections underneath the mass of the sphere, helping create a wonderfully welcoming public plaza (underneath approximately 12,000 tons of concrete).

More on the award-winning precast linked here.